Thousands more Australian and New Zealand businesses face stringent obligations under new requirements aimed at tackling modern slavery.

Professor John McMillan’s review of the first three years of the Modern Slavery Act, which was tabled in Parliament in May, makes 30 recommendations to combat modern slavery.

Key amongst these is extending reporting obligations to entities that have an annual revenue of $50 million, lowering the threshold from $100 million. In New Zealand, firms with NZ$20 million in annual revenue will be required to report on worker exploitation risks in operations and supply chains.

An October general election is unlikely to slow down New Zealand’s stance, given cross-party support - and Labor made pre-election commitments to tackling modern slavery, suggesting the McMillan recommendations are likely to be accepted by the Albanese government.

The fact that $8 million in funding to create an anti-slavery commissioner was announced in the Federal Budget in May only adds to this line of thinking.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus told a conference in Melbourne in June that the government was scoping the role and functions of the commissioner and exploring the need for legislation to establish one.

His office has also this week released a review of Division 270 of the Criminal Code, which ‘criminalises slavery and slavery-like practices including servitude, forced labour, deceptive recruiting, debt bondage and forced marriage’.

This report notes the law is robust in Australia, though it adds it ‘could be further modernised to ensure they remain future-proof’. While corporates face civil penalties for breaches, it’s clear tackling modern slavery will become an extra level of governance for many.

Fiona Reynolds, who is on the advisory committee for the Australian Human Rights Institute and the advisory board for the NSW Anti-Slavery Commission, welcomes the moves.

“For the first time, we will have a full-time commonwealth-level role looking at, reviewing and monitoring the issue and making recommendations to the government,” she says.

Activists’ figures show that there are more people living in slavery that at any time, including when it was legal.

And it is also clear that modern slavery is not just a problem for other jurisdictions.

In its latest Global Slavery Index published last month, the Walk Free human rights group estimated the number of people living in modern slavery in Australia was 41,000.

Worldwide there was an estimated 50 million people were living in modern slavery on any given day in 2021, a jump of 10 million people since 2016, according to that report. Of these, 28 million were in forced labour and 22 million were trapped in forced marriage.

The McMillan review’s recommendations include introducing penalties for non-compliance with the statutory reporting requirements and a formal public complaints mechanism as well as requiring entities to report on modern slavery incidents or risks.

But which recommendations will have the most consequences for business?

Antony Crockett, a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills, believes a mandatory requirement to implement a due diligence system is the recommendation likely to have the biggest impact on the financial services sector.

Currently, companies only have an obligation to report on their modern slavery risks and the steps taken to address these.

If introduced, Crockett says the due diligence requirements are likely to be considerably more onerous than the current reporting obligations and would require more compliance investment in policies and systems.

However, the review also recommends introducing a three-year reporting cycle, rather than the current annual one, a move Crockett believes will be welcomed by larger financial institutions that have to consult entities within their group structure before reporting.

Lowering the reporting threshold from companies with a consolidated annual revenue of $100 million to those with $50 million will mean a further 2,400 organisations will be required to submit reports, according to Reynolds, who also chaired the global commission on Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking (FAST). Some Australian law firms suggest the figure could be much higher.

Of those SMEs drawn into a need to report, some will be in financial services and could include smaller funds, asset managers, financial planners and specialist lenders that may not have the sophisticated human rights policies and due diligence systems that larger institutions have.

Nonetheless, Abigail McGregor, a partner at Norton Rose Fulbright Australia, says the lower threshold could assist bigger financial institutions. A larger part of their customer base will now be engaging with modern slavery risks and there will be more information available on whether to proceed with a particular customer, loan or investment.

McGregor suspects that the anti-slavery commissioner will have to provide some guidance to deal with the risks of index funds that have to invest in every entity on, say, the ASX 200 and whether they'd have to undertake due diligence on all of them.

“It will also be interesting to see how the global financial institutions that operate in Australia via foreign registered entities are affected,” adds McGregor.

“Often, they're not as progressed as Australian entities about their programs because Australia is just one of many different jurisdictions in which they operate.”

Reynolds believes investment managers can expect many more questions from superannuation fund clients on how they are monitoring modern slavery risks, their reporting and what actions they take once they identify modern slavery.

“Similarly, banks can expect many more questions from their shareholders. There will also be greater scrutiny from the media due to the increased reporting,” she says.

“Insurers will also be asking more questions and expecting more reporting to ensure that they are not falling foul of the law.”

On the supply chain side, McGregor says financial institutions will have to report on a range of factors.

These will include everything from the cleaners they use and where new office furniture or computers come from.

“These are issues that need to be managed, but the risks are not as great as if you're buying coffee beans, for example, from companies that potentially have slaves in Africa,” she says.

Crockett believes the tougher reporting obligations and a mandatory due diligence obligation could potentially deter outsourcing. “I have seen at least one example already of a client deciding not to outsource certain back-office functions due to human rights considerations, including modern slavery considerations,” he says.

Overall, Reynolds observes that Australia’s financial services sector has become increasingly used to higher transparency and reporting requirements in ESG areas.

“On a high-profile issue like this, I think there is an understanding that more scrutiny is the general direction of travel,” she says.

“There's also a growing social and community expectation that the finance sector must be active on modern slavery.”

But she adds that the industry has been working on modern slavery for many years yet hasn’t solved the problem.

“In fact, the problem is growing. Today there are more people in some form of modern slavery than at any time in the world’s history, including when slavery was legal,” she says.

“We need to do more. We are failing many of the most vulnerable people in the world due to a lack of oversight and implementation, and by an out-of-sight, out-of-mind approach.”

Planned legislative changes in New Zealand underscore the need for more work done by businesses to ensure they are not supporting modern slavery.

In July, the government announced it was starting work on a supply chain register to crack down on modern slavery.

Companies with revenue of NZ $20 million a year would need to report how they had tackled exploitation risks in their operations and supply chains.

Those failing to provide information for the register face fines, ranging from NZ$10,000 to NZ$200,000.

Free trade agreements with the EU and UK dictate more due diligence by government and business.

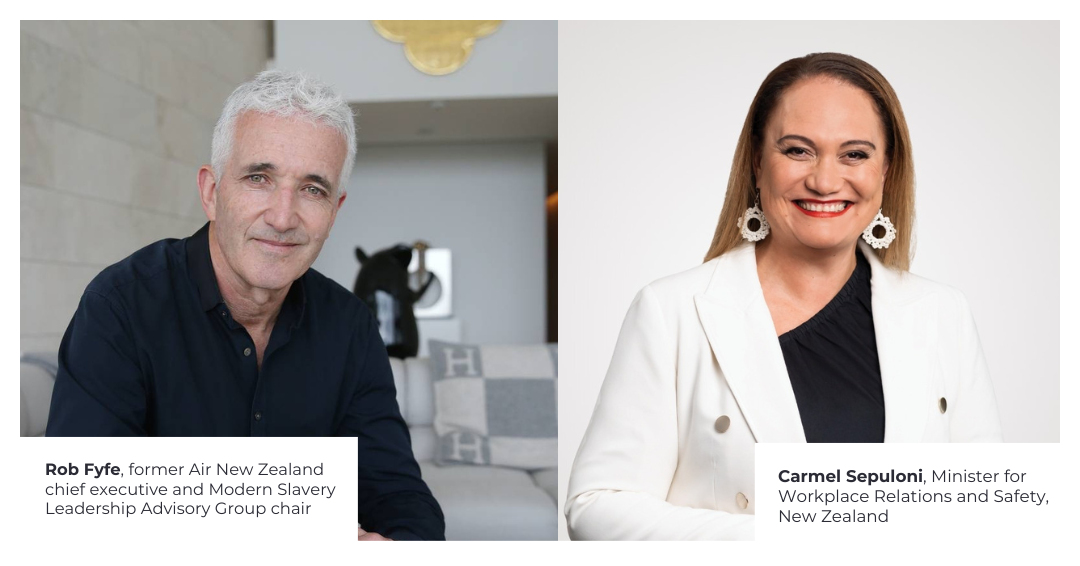

Former Air New Zealand chief executive and Modern Slavery Leadership Advisory Group chair Rob Fyfe, who helped launch the new crackdown with Workplace Relations and Safety Minister Carmel Sepuloni, said he admired businesses who were already taking the lead in addressing modern slavery.

“But we must create a level playing field and ensure that as business leaders,” he said.

“Our quest for cost competitiveness does not come at the cost of enabling modern slavery practices within our operations and supply chains”.

“My experience working with companies both in New Zealand and internationally has shown me just how important it is to know your operations and supply chains, and the value you can add to your business and brand through doing good business.”

Noting that more and more we are seeing consumers demanding transparency on the products they buy, he added: “The challenge consumers currently have, is that there is no easy way to find out what’s going on in the supply chains.

“There is no way to know what went into making the clothes they’re wearing. This reporting system will help bring this information to the fore.

“These important changes bring us in to step with a number of our key trading partners the growing expectations of our domestic and international consumers.”

Tim Murray, founder and CEO of SlaveCheck, which provides a SaaS-based modern slavery due diligence system, says he is impressed by the way Australian governments are becoming recognised as global leaders in tackling modern slavery.

But he adds the flip side of this for business is that – as governments around the world progressively raise the compliance bar to ratchet up pressure on corporates to address modern slavery, it’s going to get a lot tougher for corporates.

“I can see two interlinked reasons why many companies and boards feel like they’ve been backed into a corner with modern slavery compliance,” he says.

“The first is the fact that it’s all quite new. The world only started to mobilise in 2015, spurred on by UN Sustainable Development Goal 8.7 to eliminate slavery by 2030. In Australia, it’s only been four years.

“So it’s very immature with little specialised supporting infrastructure.

“The second reason is that the legislation makes bigger companies responsible for compliance.

“What has developed, quite unfairly, is the expectation that these reporting entities have to fix the problem by themselves, which they can’t.

“For business, with the right supporting infrastructure and with compliance activities being shared equitably around the modern slavery stakeholder community, I can see modern slavery compliance becoming less about regulatory risk and more about business as usual, continuous improvement and the strategic benefits that can flow from this.”

Consumer research carried out by SlaveCheck showed 92% of those surveyed believed it was the responsibility of a business to know if their products are produced by slaves.

“There’s a business case in getting compliance right. A field study carried out in Gap Jeans by Harvard University showed 14% higher sales for products labelled ‘ethical labour’”.

Clearly, increasing regulatory requirements and consumer demand will push modern slavery up higher up Boards’ agendas.