When APRA awarded a restricted ADI license to Islamic Bank of Australia in July 2022 - it was only the second ever local deposit institution seeking to offer Islamic banking and finance products to this sector.

But in a special two-part series, MCCA Islamic Finance and Investments Executive Director Kingsley David explains how the sector that started in humble beginnings is one of fastest-growing areas of financial services serving more than 800,000 customers.

Humble Beginnings

A residence in Melbourne’s middle income South-eastern suburbs…

A fellowship – pun intended – of twenty likeminded Australian Muslims gathered on a weekday evening in February 1989.

Pledges of hard-earned monies by each of those present as member share capital towards incorporating a registered trading co-operative that’d provide Shariah certified financing to its members

… or so the story goes.

In 1989, Islamic Finance as a globally distinct sector did not exist, Australian Muslims numbered less than 145,000 and as the newest migrant community were likely amongst the lowest ranked demographic in terms national of household wealth and income benchmarks… clearly, logic and economic reality weren’t the motivating factors for those founding members.

The Co-operative seeded that day, the Muslim Community Co-operative (Australia) Ltd, sprouted a distinct and thriving market segment where today more than five providers – led by MCCA Ltd, the segment dominant successor entity to that pioneering co-operative – service a faith aligned demographic numbering more than 813,000 individuals, who are younger and organically growing faster than the wider population.

What’s Islamic Finance?

Having had countless conversations with commonwealth and state regulators, brand name funding partners and service providers over the past 29 years on what Islamic Finance is and isn’t, I’ve found that a financially literate audience is best served by comparing the conventional approach and the Shariah certified approach in the context of a particular financing situation.

But let’s first get some definitions and key concepts out of the way.

Shariah

May be defined as the body of Islamic law derived from the primary sources of the Holy Quran and the recorded Prophetic traditions as interpreted for application by recognised religious scholars, both historical and contemporary.

It is these contemporary scholars that certify whether a particular financial product currently offered is Shariah compliant within the context of its social and business environment.

The application of Shariah to any fact situation by a qualified scholar may be viewed as similar to how court judgements are handed down in English law jurisdictions such as Australia; applying a prevailing precedent to a similar fact situation or deriving a new precedent where no applicable precedent is found to the fact situation at hand.

Maslaha

Similar to English law, Shariah also recognises ‘Public Interest’ as a legitimate reasoning input to deriving judgements.

It is noteworthy that most qualified local and international Shariah scholars consider the practice of Shariah certified residential property financing in Australia to be in the public interest of Australian Muslims.

Key prohibition on usury

Whilst there a number of other prescriptions that apply to financial transactions under Shariah, by far the most significant in the Australian context is the prohibition on usury.

Simply put, any nominal value differential in a current AUD cashflow-for-deferred AUD cashflow exchange (i.e., any amount beyond the nominal ‘principal’ AUD amount) is typically viewed as usurious in Shariah.

Cue the frowns and disbelief.

“But don’t Shariah based banks and financiers operate commercially for-profit?... and in a largely harmonized Basel prudential environment, no less?”

Yes, they do.

So, how is a commercial benefit derived by a funder in a Shariah certified financing transaction?

Illustrative comparison

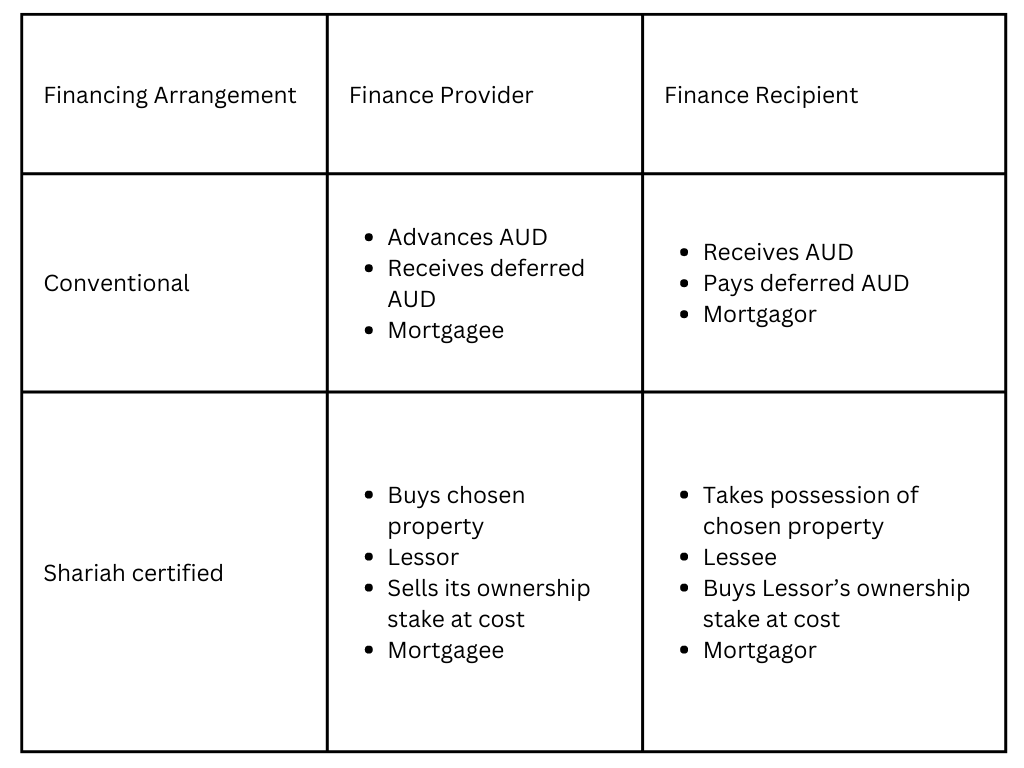

Let’s compare how an Australian consumer residential property finance transaction would work conventionally and under a likely Shariah certified product.

Firstly, the similarities.

Intent of the Parties

The finance provider in both instances makes a secured, ‘for-profit’ financial accommodation to enable the finance recipient to undertake the purchase, possession, and ultimate ownership of their chosen Australian residential property.

Cashflows

The cash flow profiles under both arrangements would be identical, with the Finance Provider disbursing a current AUD cash flow and the Finance Recipient contracting to disburse a predictable future series of periodic AUD cash flows that (typically) would carry a greater nominal value than that received.

Registered Mortgage

In both cases, the rights of the Finance Provider (and the performance obligations of the Finance Recipient) are secured by a first ranking registered mortgage over the chosen property.

So far, so good; identical cash flow profiles, identical mortgage enforceability rights and identical core purpose.

Time to introduce another key concept; Shariah certified asset financing (such as residential property finance) typically requires an asset exchange, in parallel with the cash-for-deferred cash exchange, as an intrinsic part of the transaction.

If one was to revisit the overarching prohibition of usury (i.e., any monetary excess on a money for money exchange), it should be readily appreciable that a transaction where an underlying asset was traded in parallel would fall outside that definition and would (subject to also complying with the other prescriptions) therefore broadly be Shariah certifiable as the monetary excess would be in the nature of rental or profit on sale.

Very obviously, the current framework of Australian financial services and other applicable regulations, industry codes and practices, particularly as applicable to consumers, raises a number of challenges for anyone seeking to develop and offer, say, a dual (i.e., local regulation and Shariah certified) compliant consumer residential finance product.

I look forward to sharing how these challenges may be addressed in Part 2.